Extinction Studies

Extinction Studies

2019 - ongoing

Works on paper

“(If) another era of equal human crime and human improvidence were to take place, total extinction of the human species was quite possible.” - George Perkins Marsh, 1854

In 1892, New York State Governor Roswell P. Flower signed the law creating a 2.8 million-acre Adirondack Park to be protected from uncontrolled deforestation. The "blue line" was intended to delineate the boundary within which future forest preserve acquisitions should be focused.1 Today’s Adirondack Park is a six-million acre patchwork of public and private lands located in northeastern New York. It’s a region of the forests, farmlands, waters, wildlife, and communities of people co-existing together. From the conservation perspective, it’s one of the kinds, sort of an experiment in conservation that has been going on for over 130 years.

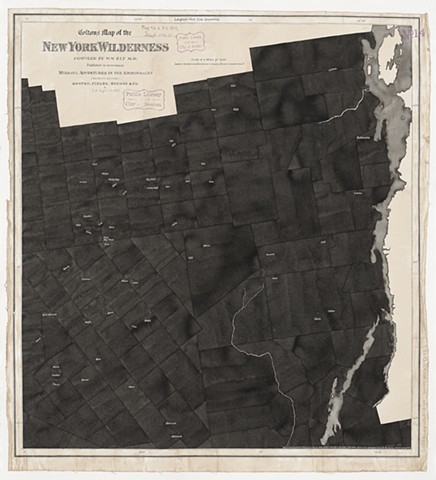

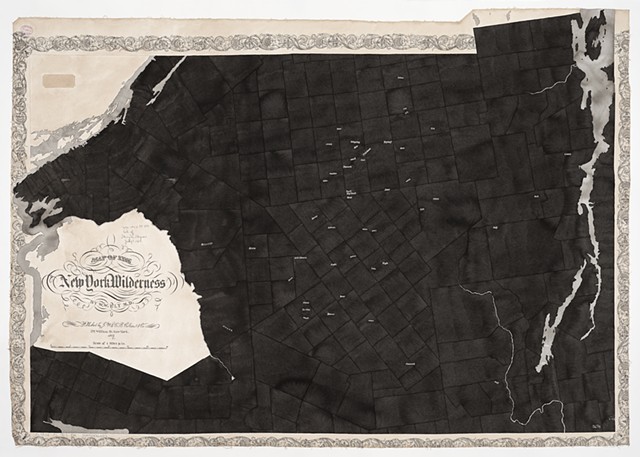

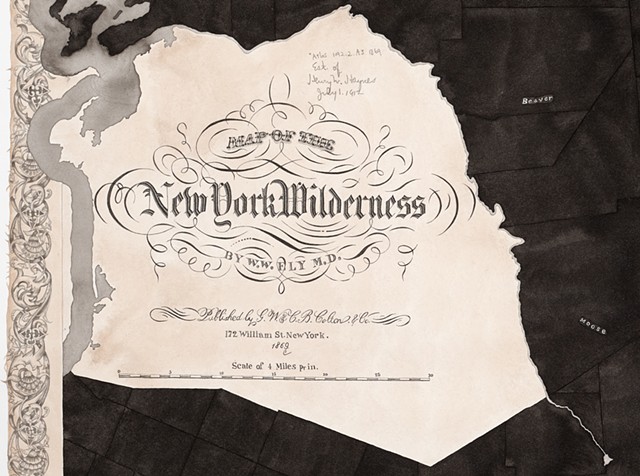

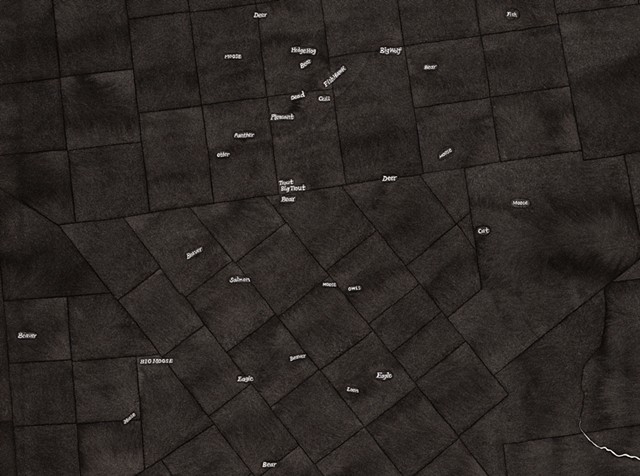

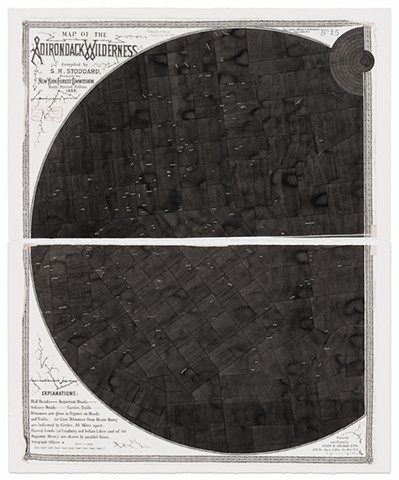

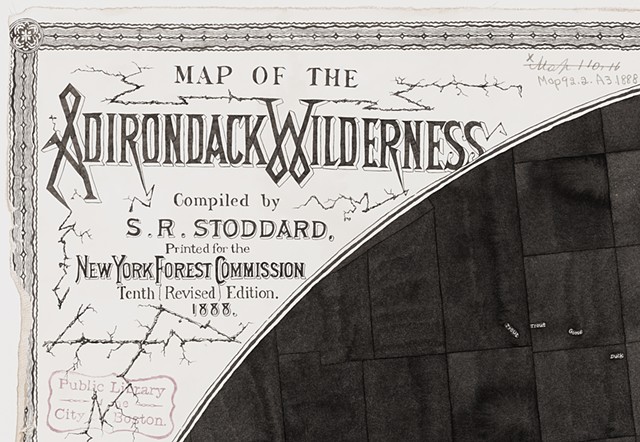

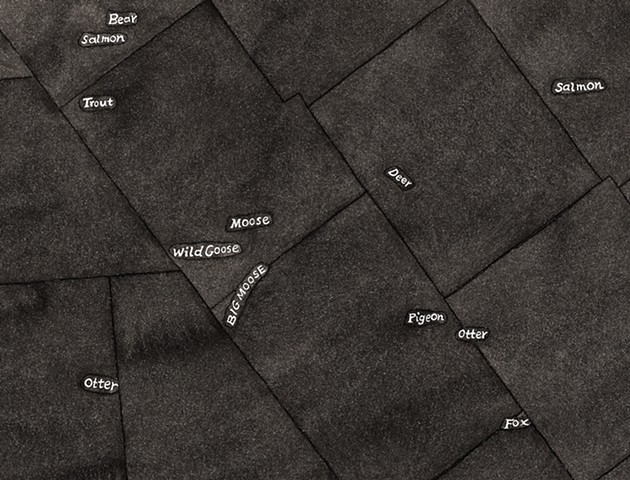

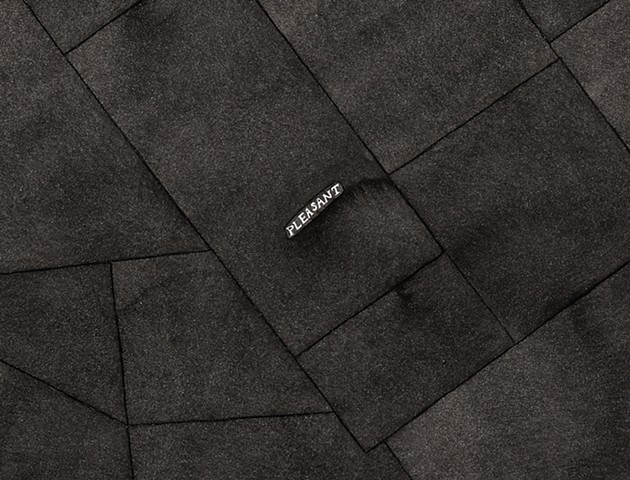

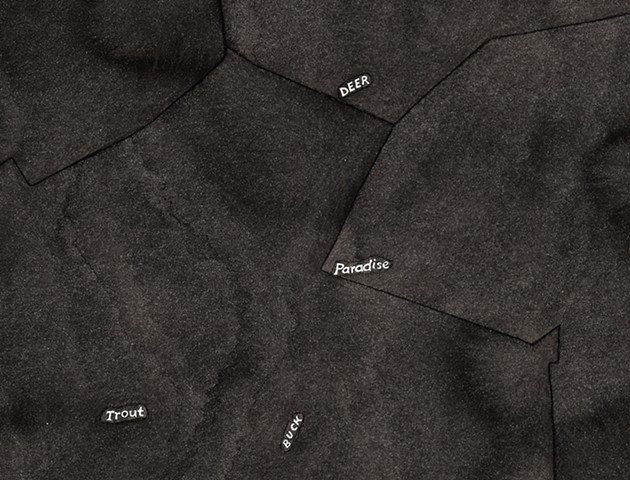

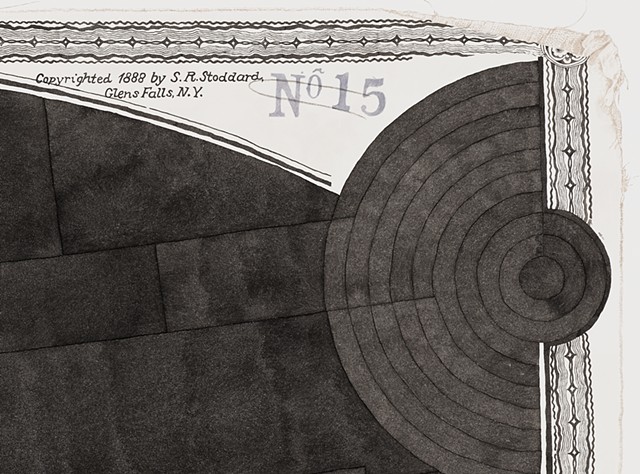

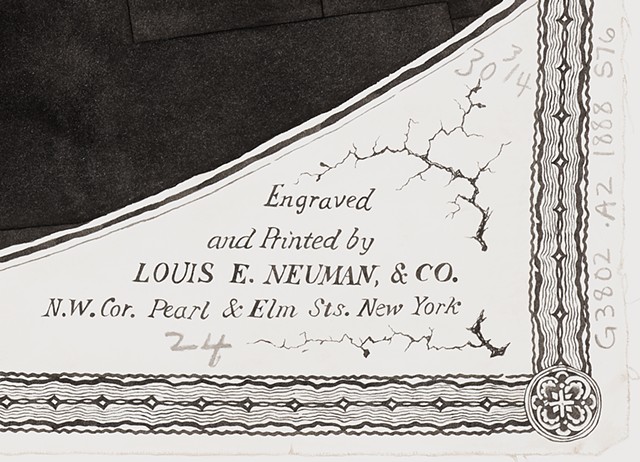

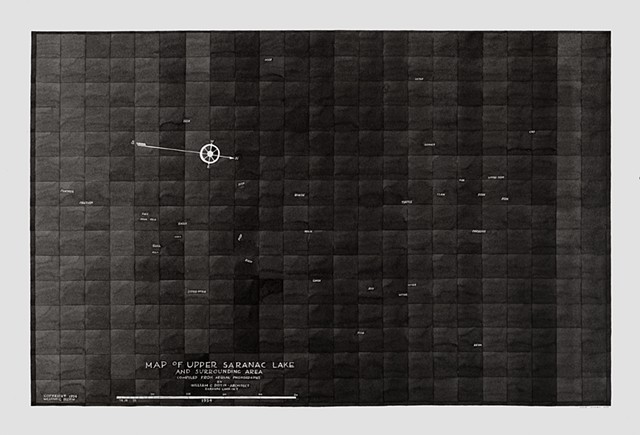

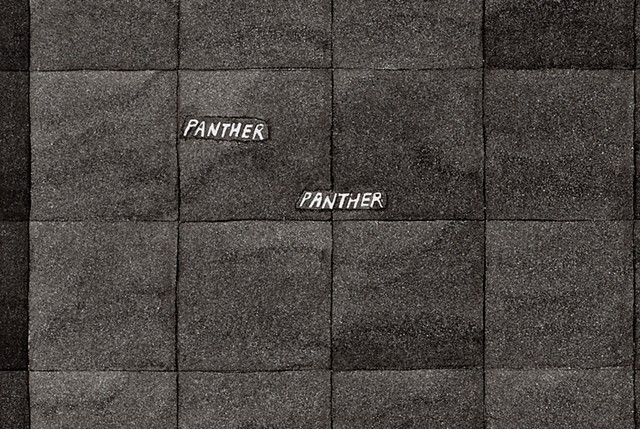

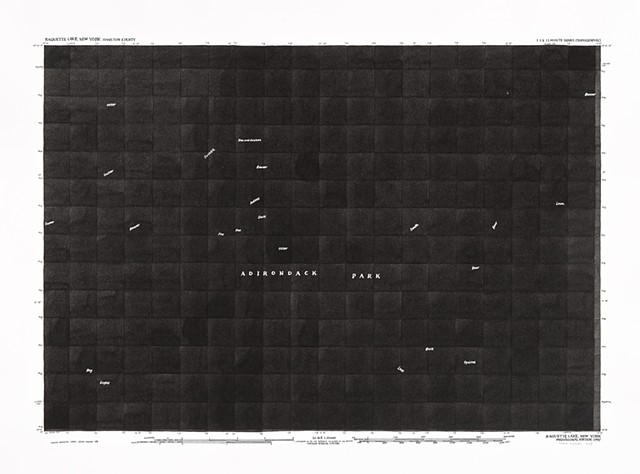

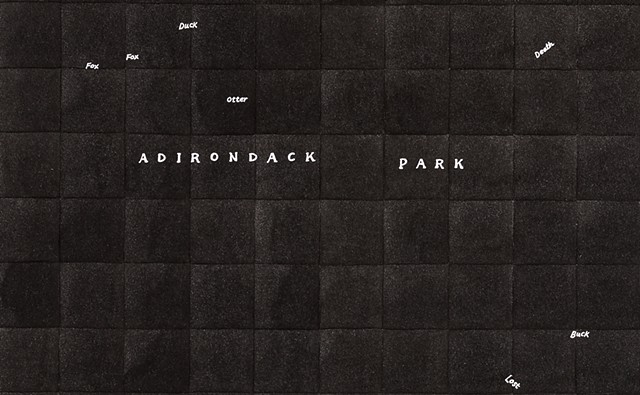

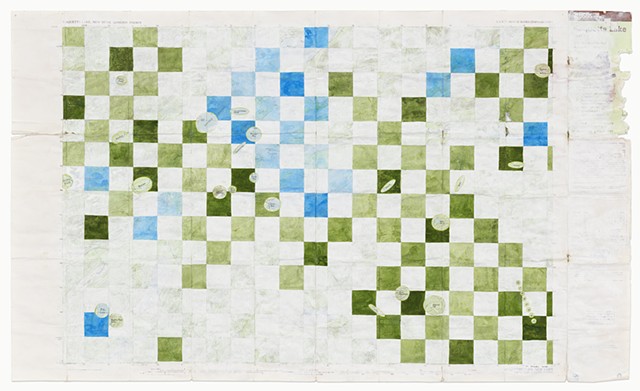

Extinction Studies is an ongoing series of drawings based on historical maps of the Adirondacks in Upstate New York. Monochromatic black ink drawings are created by tracing copies of the original maps by hand. The drawings include the names of geographic areas that were named after the wildlife, such as “Eagle Lake,” “Little Otter Pond,” “Buck Mountain,” “Beaver Brook,” and “Salmon River,” but I choose only the animal names to be visible. These texts were not painted but left untouched to reveal the white of the paper. They float as tiny white specs in a sea of blackness, as if to form new constellations in the sky. Some selected cartographic information such as the titles and borders are made visible by faithfully copying the original map.

I was first introduced to the Adirondacks region in 2005 when I attended a month-long residency at the Blue Mountain Center. I fell in love immediately by its natural beauty—lakes and endless waterways, mountains, and wildlife. This is where I learned to swim in open waters in Eagle Lake, and my experience with their waters changed me completely. My work took turn to focus on water, and gradually I became interested in the history of the Adirondacks and its intertwined relationships with the legacy of colonialism and the conservation efforts to undo the damage and to preserve “forever wild.” It was a remarkable event to establish such a large region as protected land where people could also inhabit. And it was remarkable because it was prompted by the public outcry over declining water quality and the deforestation of the land in the Adirondack region.

Wilderness was already in decline from wide-spread deforestation by the 1850s as the European settlers cut down trees for lumber, charcoal, paper, tanning, and iron ore mining—all for profit and financial growth. Conservation efforts were already needed by then due to the considerable damage done.

In 1854, George Perkins Marsh who is considered to be America’s first environmentalist published Man and Nature, an instrumental move to preserve the Adirondacks by raising awareness about the many ecological consequences from deforestation, diminishing capacity to hold water from loss of wetlands, accelerating runoff, and soil erosion. Marsh warned that if “another era of equal human crime and human improvidence were to take place, total extinction of the human specifies was quite possible.” In the midst of the climate crisis and mass extinction, Marsh’s words from over 150 years ago echo with the most alarming tone. Humans are capable of turning a blind eye to what has been wrought in the pursuit of capital.

The success of the Adirondacks Park for preserving and conserving their once devastated land shows that nature could bounce back with great care. It was possible then. Is it possible now? And protected regions such as the Adirondacks Park and National Parks are not exempt from climate crisis or loss of biodiversity either.

Many scientists have been warning us about the loss of biodiversity for decades, and claimed that the world entered its sixth mass extinction event, the first since 66 million years ago when more than 80% of all species, including the non-avian dinosaurs, perished. In the 2017 study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists describe the global species extinctions as a “biological annihilation” that will lead to “negative cascading consequences on ecosystem functioning and services vital to sustaining civilization.”2

While studying the maps of the Adirondacks, I became obsessed with finding names of wildlife on the maps. I try to find them with a magnifier as most of them were printed in tiny font size. And this act alone made me think of our possible future—where a vast wildlife may be gone or incredibly difficult to find, or even perhaps, we may only remember them just by names, like so many other extinct animals.

For examples, wolves were abundant but they went extinct by the end of the nineteenth century as bounties were set on removing this species. The last wolf was believed to be killed in the Adirondacks in the late 1890s until recently. The 2011 study found that a wolf was killed north of Great Sacandaga Lake in 2001, however, if wolves are currently living in the Adirondacks, the numbers are believed to be extremely low.3 Wildlife removal of the nineteenth century resulted in decline or extinction of wolves, moose, and panthers by the mid-century.4 Beavers became almost extinct in the Adirondacks by 1840 from intense beaver fur trade and deforestation until they were reintroduced between 1901 to 1907, and became abundant again.5 In the recent decades, the impact of acid rain led acidification of lakes and mercury contamination of water bodies, which threatens many fish and aquatic life as well as some native trees such as sugar maple in the Adirondacks.6

In this series, I’m working my way towards finding a 1771 map where the Adirondacks region was shown as blank space as unknown and unexplored to the early Europeans. Their perception of the region was “of a vast, inhospitable wilderness” and “devoid of human connection” with nature.7 I have not yet found a digital image of this map. Of course, humans have inhabited this region since 15,000 to 7,000 BC along with wildlife.8 The first Iroquoian peoples (the Mohawk and Oneida) arrived in the Adirondack region between 4,000 and 1,200 years ago. The region was called “Dish with One Spoon” by Indigenous peoples. It symbolized shared hunting resources between groups.9

After the English replaced the Dutch and renamed New Netherland to New York in 1664, logging operations began and land was cleared for farming in this region removing “the cover that provided a haven” for Indigenous people for thousands of years.10

Notes:

1. “Birth of the Blue Line” brochure, Department of Environmental Conservation.

2. Ceballos, Gerardo, Ehrlich, Paul R., and Dirzo, Rodolfo. “Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines.” in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 114 | No. 30. July 25, 2017. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1704949114

3. “Adirondack Gray Wolves” in Adirondack.net. https://www.adirondack.net/wildlife/wolves/ Retrieved on Nov. 28, 2019.

4. Schneider, Paul. The Adirondacks: A History of America’s First Wilderness, 85. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

5. ibid

6. Gast, Richard. “Acid Rain Still Impacting Adirondack Lakes and Forests” in Adirondack Almanac. https://www.adirondackalmanack.com/2017/08/acid-rain-still-impacting-adirondack-lakes-forest.html

Retrieved on Nov. 28, 2019.

7. Adirondack Mountain. Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adirondack_Mountains, Retrieved on Nov. 27, 2019.

8. ibid

9. ibid

10. History of the Adirondack Park. Adirondack Park Agency website: https://apa.ny.gov/about_park/history.htm, Retrieved on Dec. 5, 2019.